It's unlikely that the Arab traders who plied their business down the east African seaboard ever visited the Falls but their goods found their way to the area through middlemen.

Although the Portuguese established forts in Mozambique by the 17th century and explored large areas of the lower Zambezi, there is no record of Victoria Falls being known to the outside world until the middle of the 19th century.

The colonial writer George Lacy wrote that Englishmen in South Africa first became aware of Mosivatuna, the "smoke that sounds" in 1840. Bechuana hunters returning from northern Botswana told of the stories they had heard from San hunters about this astounding phenomenon where there was a continual presence of smoke emanating from the river gorges.

These hunters' tales were reaffirmed in 1851 by the missionary explorers David Livingstone and William Cotton Oswell while on their expedition to the upper Zambezi. On that occasion, they heard of the Falls but did not have the opportunity to visit them.

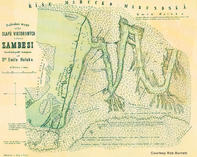

Interestingly, the Falls were correctly located on the 1852 map in William Desborough Cooley's book, Inner Africa Laid Open, a good three years before Livingstone first set eyes on them. Cooley's map was, however, riddled with other errors, principally that the upper and lower Zambezi were reflected as separate rivers.

It's not clear who Cooley's cartographic sources were, but he did not get his information from either Livingstone or Oswell. Among the contenders who may have seen the Falls before Livingstone are the Portuguese trader Silva Antonio Francisco Porto, who travelled through Barotseland in 1848 or the Hungarian Ladislaus Magyar, who reportedly trekked through the region in 1851. However, if either of the men saw the Falls, they left no record of it.

It was David Livingstone's report of visiting the Falls that had a dramatic and lasting impact on the outside world. By that time, he had already established a sound reputation as a missionary explorer, which had earned him widespread recognition and support. During his 1853 expedition to try to find a route across southern Africa from west to east, Livingstone decided to find the Falls of which he had earlier heard.

It was only two years later, in November 1855, that he managed to get the chance. Along with Chief Sekeletu of the Mokololo and 200 of his supporters, Livingstone travelled down the Zambezi from what is now Sesheke in western Zambia. They were forced to abandon their canoes at Katambora rapids and decided to walk the rest of the way.

The historian DW Phillipson wrote that: "Two days after leaving Old Sesheke, Livingstone reached Kalai Island on which he saw where Sekute was buried in a grave surrounded with a fence of 70 large elephant tusks. After a night on the island, Livingstone set out to visit the Falls.

Sekeletu had intended to accompany him but, as only one canoe could be found, he had to stay behind. Livingstone reports that it was only 20 minutes after leaving Kalai that he first caught sight of the rising columns of spray, which he compared with the smoke from a large-scale bush fire".

About one kilometre upstream of the Falls he transferred into a smaller, lighter canoe and proceeded in this to the island between the Main and Rainbow Falls which is today called Livingstone Island.

As has been widely recorded, Livingstone was astounded by the view that confronted him, from one of the most awesome viewpoints of the Falls. That night, full of wonder, Livingstone returned to Kalai Island. The following day he returned to the Falls with Sekelutu, who had not yet seen the spectacle.

That day, Livingstone planted his peach and apricot stones and coffee seeds on the island and then carved his name on a tree - one of the few times he felt so moved during his expeditions in Africa to indulge "in this piece of vanity". Livingstone had initially underestimated the dimensions of the waterfall.

He and his brother Charles made more accurate measurements and observations in 1860. The Falls were also measured later that year by the English hunter William Baldwin, who was surprisingly close to the mark in his assessment that the Falls were 2000 yd (more than 1800m) wide and 300 ft (91m) high.

Livingstone and his brother are believed to have explored the rain forest at that time, which may have been the only crossing Livingstone made on to the Zimbabwean side of the river. Indeed, some historians believe he never set foot on the southern banks of the Falls at all!

The Portuguese major A de Serpa Pinto measured the Falls with a sextant in 1878, helped by two local (presumably deeply trusted) assistants who held him over the edge of the precipice with a cloth so that he could get his readings.

Baines noted that Livingstone's garden - grandly set up as the pioneer garden of a new country - had been completely destroyed by hippos. One of the more significant of these early "tourists" was the Czech explorer Emile Holub, who made the first detailed map of the Victoria Falls area.

Among the other explorers who followed in Livingstone's footsteps were the hunter and trader James Chapman and the artist and explorer Thomas Baines, who arrived at the Victoria Falls in 1862. Painting: "Buffaloes driven to the edge of the chasm" (1862) by Thomas Baines Courtesy: The Bridgeman Art Library

Other significant European pioneers during the 19th century were George Westbeech, a trader who was based at Pandamatenga in the northwest portion of Hwange National Park, and the missionary Francois Coillard of the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society. Both these men won the trust of the Lozi and Subiya communities, and Westbeech became an adviser to the Lozi kings.

Later, a combination of missionary persuasion and protracted visits from various imperial visitors persuaded the Lozi king Lewanika to eventually sign away the mineral rights of much of what is today Zambia, to Cecil John Rhodes's British South Africa Company, in return for a measure of independence.

In 1890, at the height of the "scramble for Africa", the region was carved up by the European powers into the sovereign territories that exist today - the Germans received what is now Namibia and the Caprivi Strip, the Portuguese took Angola, while Britain's influence predominated over what is now Zimbabwe, Zambia and Botswana.

Brett Hilton-Barber and Lee R. Berger. Copyright © 2010 Prime Origins.

The oldest-known community in the Victoria Falls region is the Kwengo, descendents of the San who were the original hunters on the Zambezi-C...

The oldest-known community in the Victoria Falls region is the Kwengo, descendents of the San who were the original hunters on the Zambezi-C...